Authors: Lujing Cen, Andreas Kipf

We are presenting LEA, our new learned encoding advisor, at aiDM @ SIGMOD 2021. Check out our presentation and paper.

In this blog post, we will be going over a high level overview of LEA. LEA helps the database choose the best encoding for each column. At the moment, it can optimize for compressed size or query speed. On TPC-H, LEA achieves 19% lower query latency while using 26% less space compared to the encoding advisor of a commercial column store.

Motivation

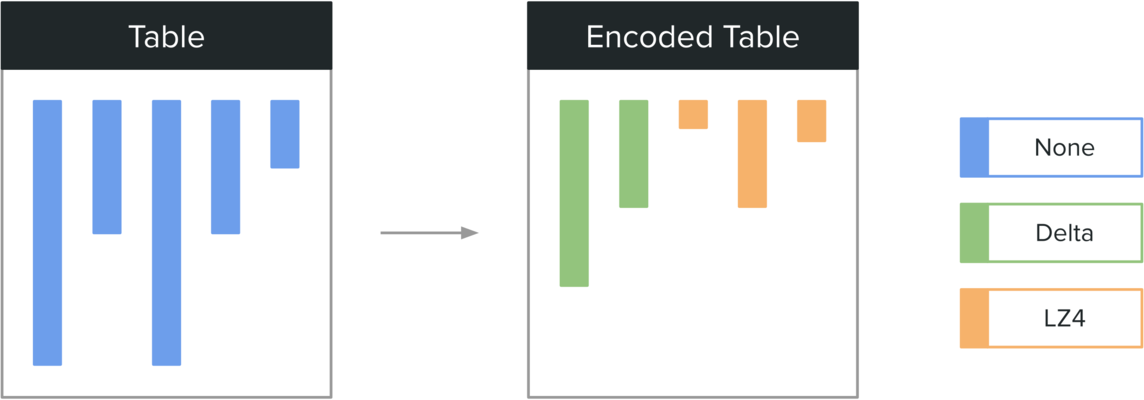

Modern databases support different encodings (lossless compression schemes) for storing columnar data. These encodings can reduce the overall storage footprint and improve query performance. A few attributes to consider when selecting a good encoding scheme are compressed size, random access capabilities, and decompression speed.

As an example, we compressed a 1 GiB CSV file using LZ4 and Gzip on a 5d.2xlarge EC2 instance with a network-attached general purpose SSD. The decompressed speed is measured in the cold-cache scenario (i.e., the file system cache is cleared).

|

LZ4 (level 1) |

Gzip |

| Compression Speed |

703 MiB |

428 MiB |

| Decompression Speed |

3.85 s |

9.45 s |

We see that Gzip achieves a much better compression ratio while LZ4 has a much faster decompression speed. This leads us to the observation that compression schemes inherently represent a tradeoff between I/O operations and CPU operations. The speeds of the underlying storage device and CPU are what determine the overall decompression speed. An encoding advisor should incorporate the tradeoffs of different encodings when selecting the best one for each column.

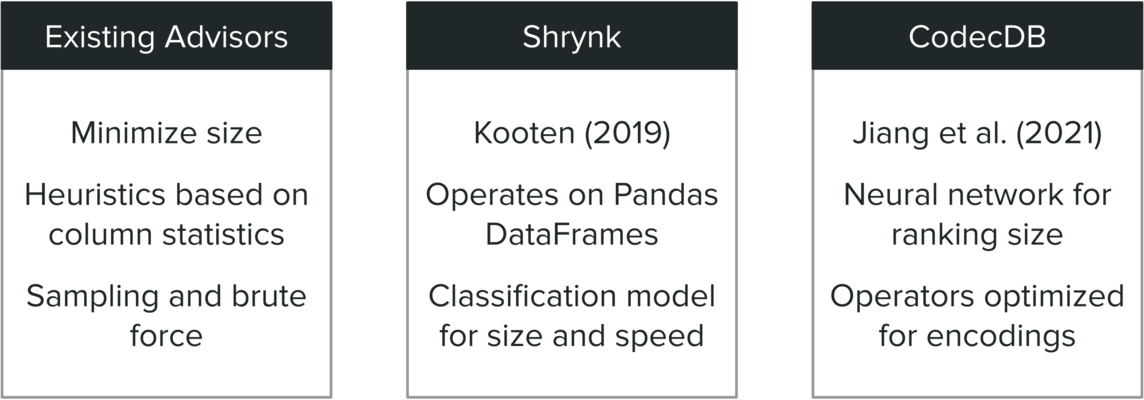

There is some work in the area of encoding selection. Existing column advisors usually try to minimize size because they assume that the storage device is much slower than the CPU, which is no longer always true. They either use heuristics based on column statistics or extract a sample from a column and try all encodings. A project known as Shrynk uses statistics from a Pandas DataFrame to build a classification model which predicts the best compression scheme to use. Concurrent work on CodecDB presents a neural network for ranking different encodings based on compressed size. It also has specialized operators which can operate on encoded columns without fully decoding the data.

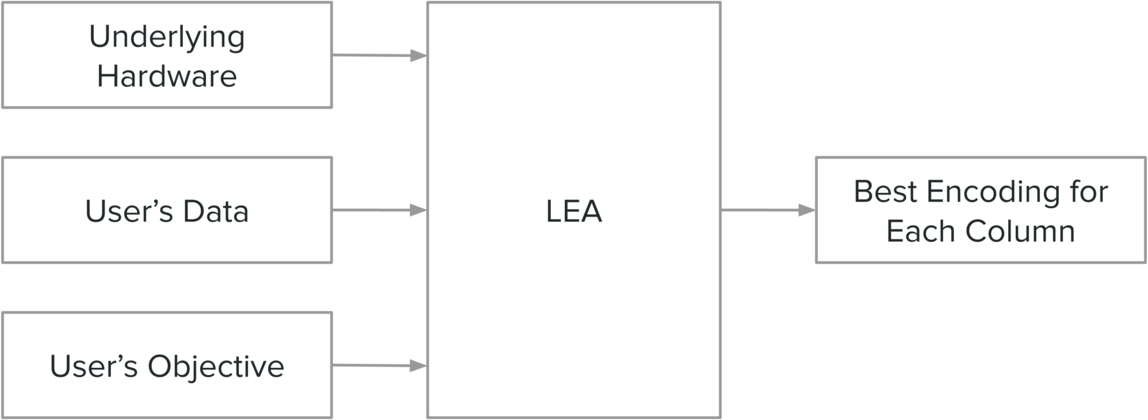

Goal

Our goal is to build an encoding advisor that takes into account the following when determining what encoding to apply for each column:

- Underlying hardware (e.g., the speed of the storage device and CPU characteristics).

- User’s data (e.g., how data is distributed in each column).

- User’s objective (e.g., minimizing compressed size or minimizing query latency).

Overview

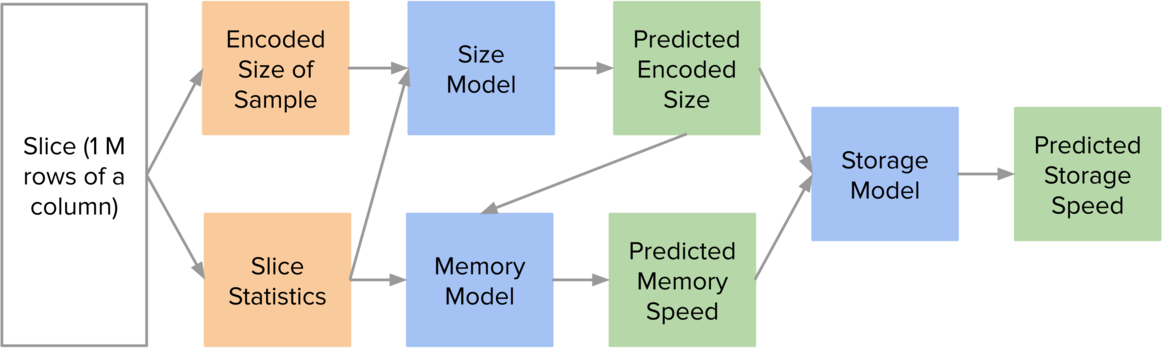

LEA operates on slices. We define a slice to be 1 million rows of a column. Each slice needs to be large enough that we can meaningfully perform experiments involving time, but small enough that we can efficiently produce many of them for training. Given a slice and an encoding, LEA predicts three properties – the encoded size of the slice, the in-memory scan speed of the slice, and the from-storage scan speed of the slice.

Here are the steps that LEA uses to obtain its predictions:

- Take a 1% contiguous sample from the slice and encode it. This will give us the encoded size of the sample.

- Compute relevant statistics about the entire slice (discussed later).

- Use the encoded size of the sample and the slice statistics to predict the encoded size of the entire slice.

- Use the predicted encoded size and the slice statistics to predict the in-memory scan speed.

- Use the predicted encoded size and the predicted in-memory scan speed to predict the from-storage scan speed.

- Repeat steps 1-5 for each slice and encoding.

- Apply an arbitrary objective to select the best encodings (e.g., compressed size, query speed, or a mix of the two).

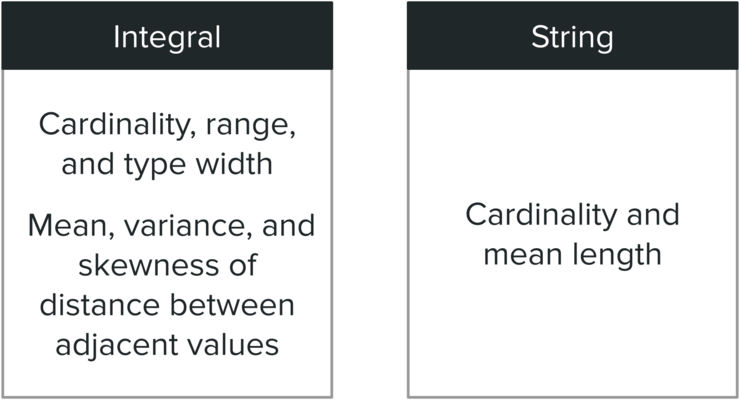

The figure above shows the slice statistics that we collect for each data type. These statistics can be computed efficiently in one pass. In addition, we found that they work well for encoding selection.

|

Integral & Short String |

Long String |

| Encoded Size |

Random Forest |

Linear |

| Memory Speed |

Random Forest |

Linear |

| Storage Speed |

Constrained Linear |

Constrained Linear |

Unlike other techniques, LEA uses regression instead of classification, which allows for arbitrary objectives that do not have to be defined during training. For integral and short strings, which we define as having a mean length of at most 64 characters, we use random forest regression for predicting the encoded size and in-memory scan speed. For long strings, we just use linear regression because random forests cannot extrapolate. For predicting the from-storage scan speed, we use a constrained linear regression to model the latency and throughput of the underlying storage device.

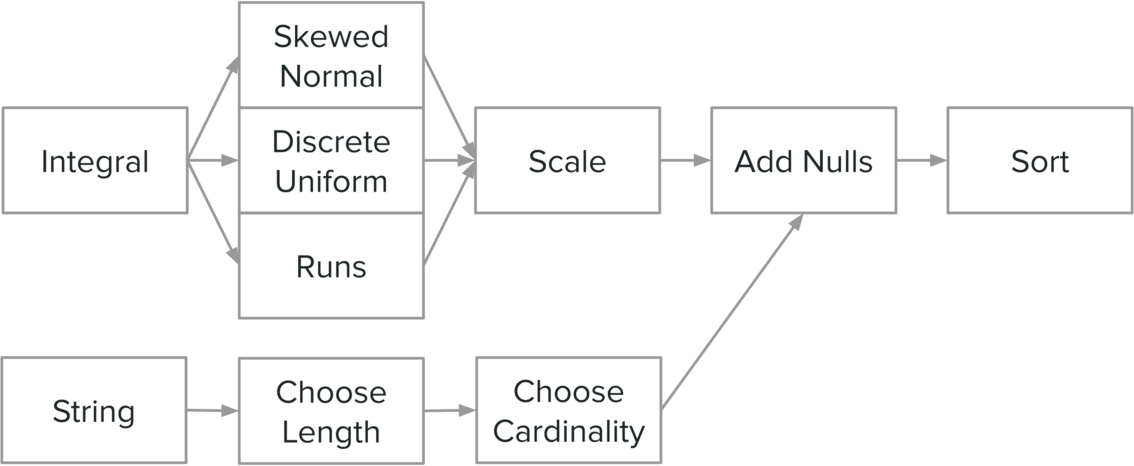

For training, we use synthetic data generated from distributions. Although it is possible to use real-world datasets, they would need to be transferred to the target system since LEA needs to measure the scan speed of different encodings on many slices. Once a slice is generated, we perform additional post-processing steps like inserting null values at random locations and possibly sorting the data to more effectively explore the input space.

Evaluation

To evaluate our technique, we compare four different strategies on a commercial column store (System-C) using the same 5d.2xlarge EC2 setup as before. C-Default is System C’s default encodings, which uses delta for integral types and LZ4 for strings. C-Heuristic is System C’s encoding advisor, which optimizes for size. LEA-S and LEA-Q are two versions of LEA which try to minimize size and query latency respectively.

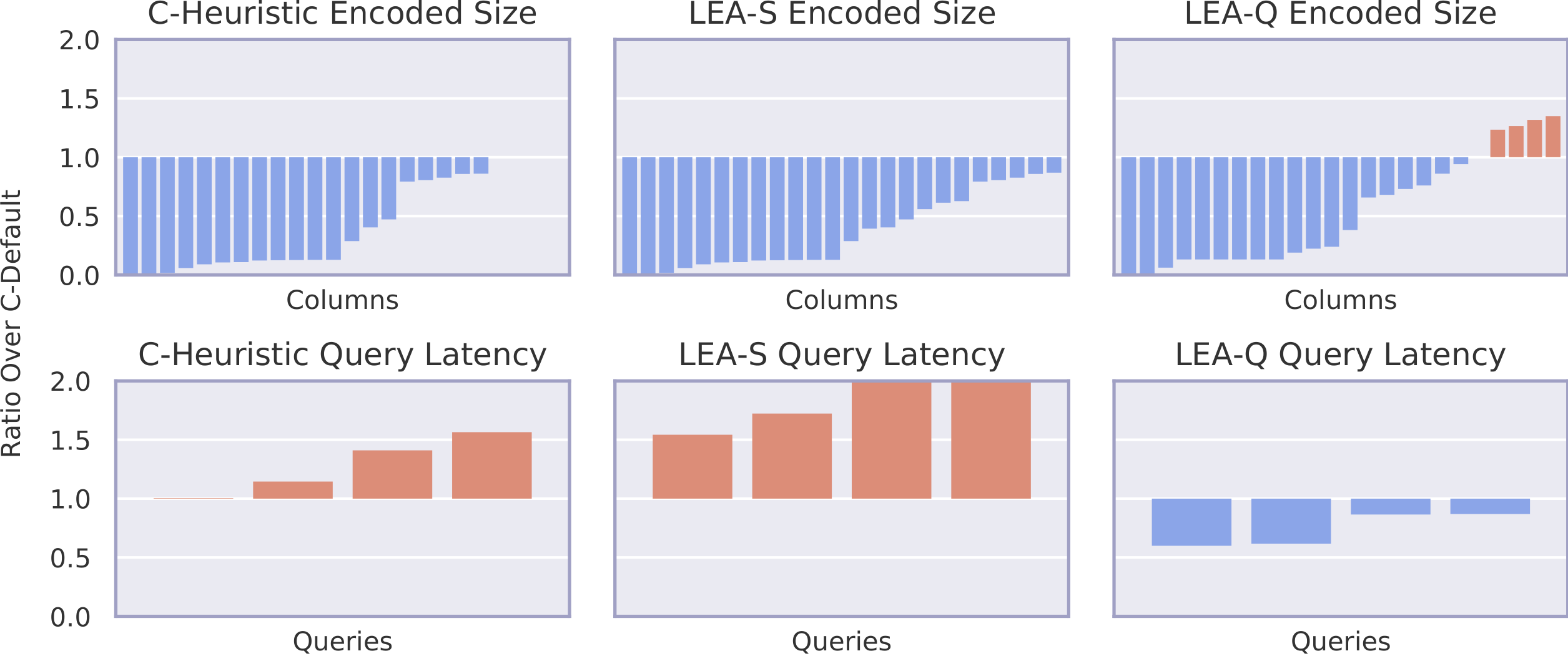

The figure above shows results for the StackOverflow workload. It consists of a denormalized table with around 12 million rows and 4 queries. The y-axis represents the ratio over C-Default. Therefore, values less than 1 represent an improvement over C-Default. Note that query latency experiments are performed with cold cache.

In terms of encoded size, we see that LEA-S outperforms C-Heuristic on a few columns. LEA-Q, which does not optimize for size, still achieves a good overall compression ratio. In terms of query latency, we see that purely optimizing for size does not lead to better performance. In fact, it can significantly slow down queries compared to using the default encodings. However, LEA-Q successfully finds encodings that improve the performance of all four queries.

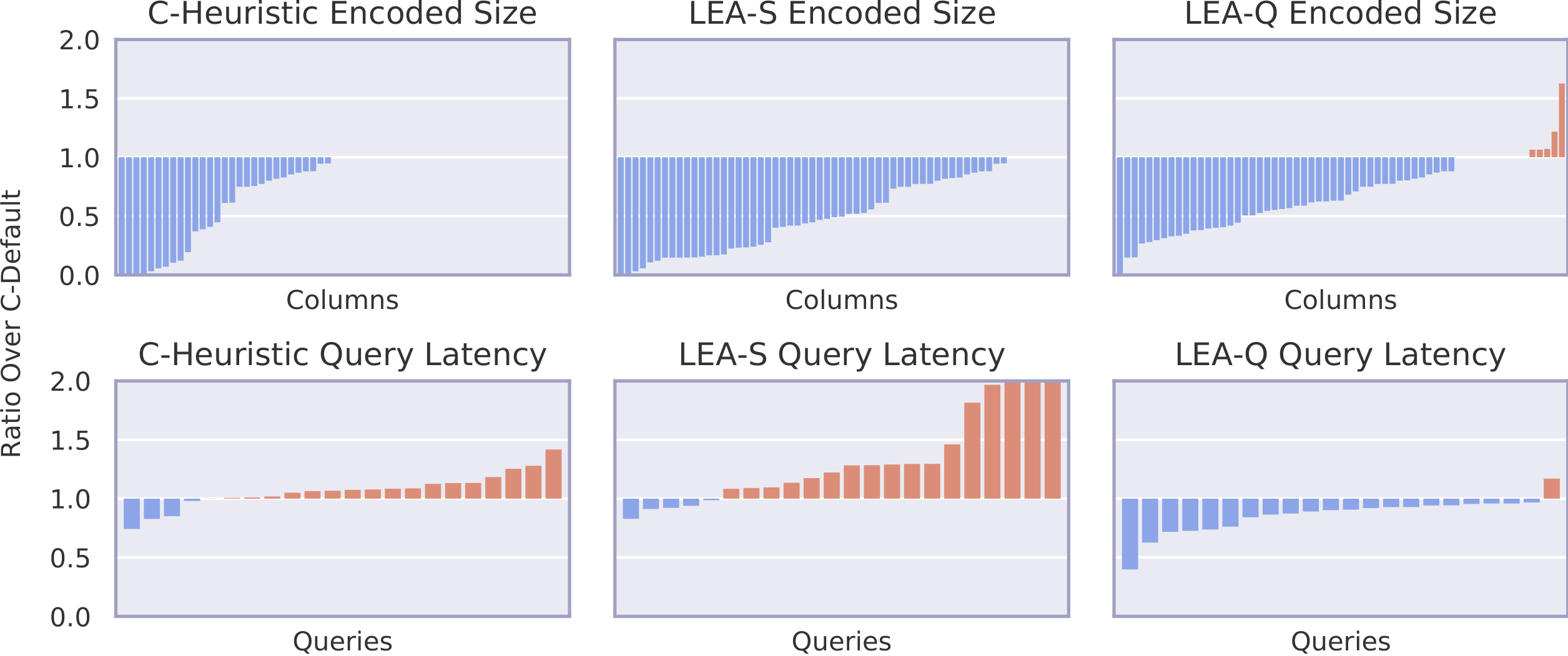

The figure above shows results for the TPC-H workload at scale factor 10. We run all 22 queries with default substitution parameters. For encoded size, C-Heuristic finds better encodings for around half of the columns, whereas LEA-S finds better encodings for around 80% of the columns. For query latency, C-Heuristic and LEA-S are both worse than the default for a majority of queries, whereas LEA-Q improves on all but one query. Overall, LEA-Q achieves 19% lower query latency while using 26% less space compared to the encoding advisor of System C.

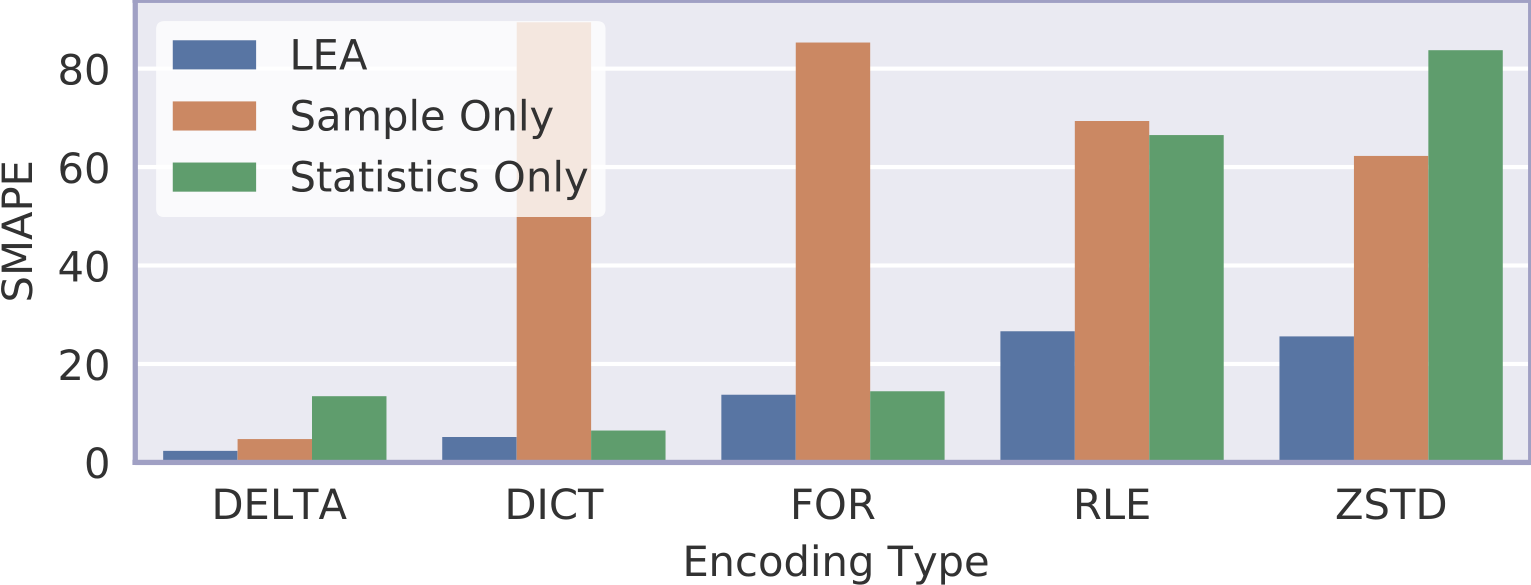

We also compared LEA against ablated versions to demonstrate the importance of using both the sample encoded size as well as slice statistics. For this experiment, we measured the symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE) of predicted values for different encodings. We see that LEA outperforms its ablated versions for all encodings. This is reasonable because dictionary encoding and frame-of-reference encoding depend on the cardinality and range, respectively, both of which are hard to estimate from a sample. However, slice statistics are less useful for more complex compression schemes like Zstandard.

Future Work

In future work, we hope to make LEA query-aware. So far, we’ve treated all columns equally. However, in an actual workload, some columns will be queried more frequently than others. In addition, the type of access will vary (e.g., sequential scan versus random access). These statistics can be extracted from the query logs.