Authors: Dominik Horn,

Andreas Kipf,

Pascal Pfeil

We are happy to present LSI: A Learned Secondary Index

Structure and our accompanying

open-source C++

implementation that

can easily be included in other projects using CMake

FetchContent.

LSI is a learned secondary index. It offers competitive lookup performance on

real-world datasets while reducing space usage by up to 6x compared to

state-of-the-art secondary index structures.

Motivation

Most learned index

structures focus on

primary indexing where base data is stored in sorted order. Since a table can

only be sorted by a single key, it is therefore of high interest to study the

feasibility of applying learned techniques to indexing unsorted, secondary

columns. Specifically, we were aiming to come up with an off-the-shelf usable

index structure that manages to retain the proven benefits of learned primary

indexes as best

as possible.

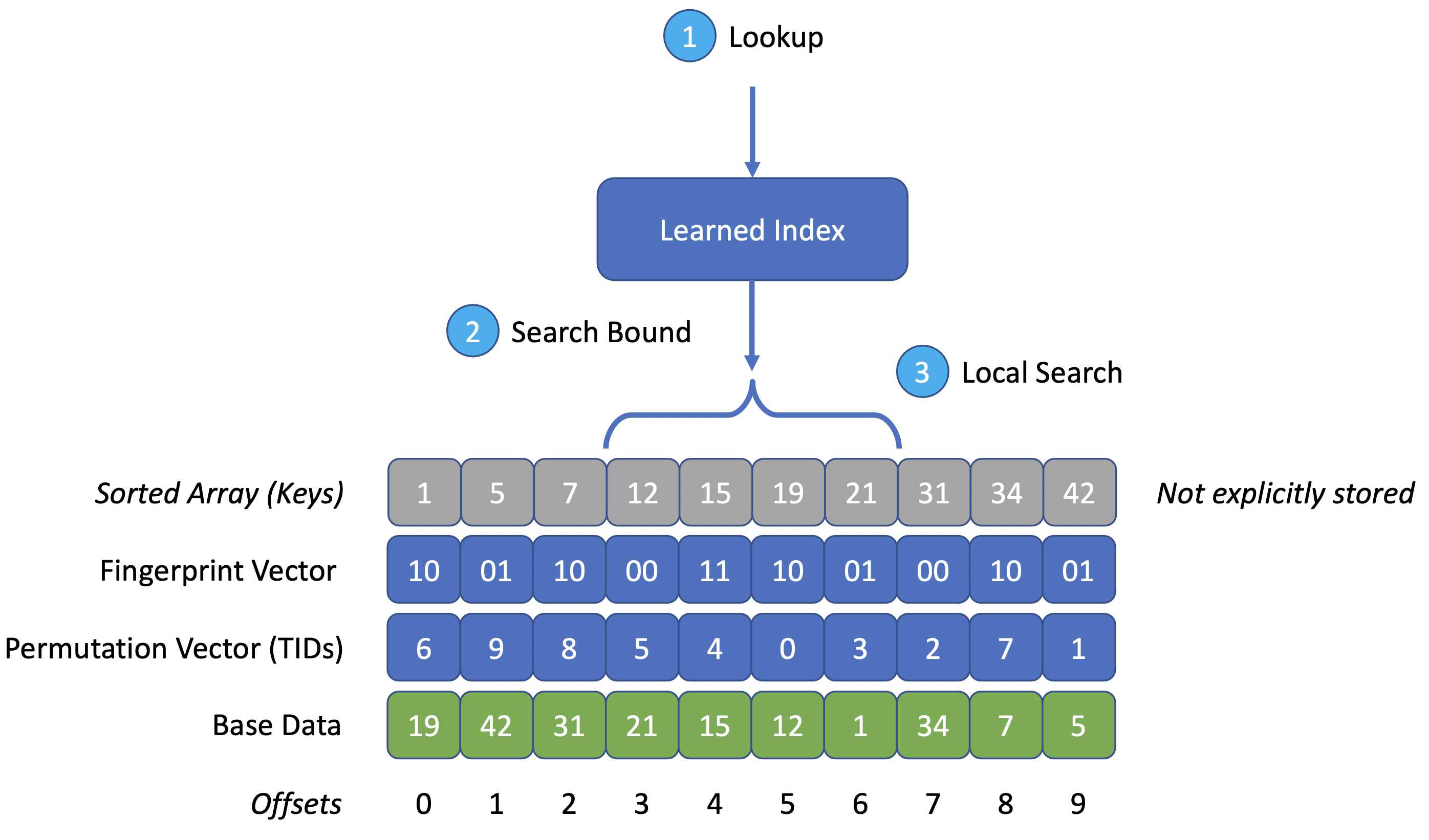

LSI Overview

LSI consists of two parts. A pre-existing learned index structure acting as an

approximate index, e.g., a PLEX, and a

permutation vector. The learned index is trained over a temporary sorted copy

of the base data’s keys. The permutation vector retains a mapping from the

sorted key’s positions to offsets (tuple IDs) into the base data. The following

paragraph contains a schematic illustration of LSI. A more detailed

explanation, especially concerning how we achieved LSI’s space efficiency, can

be found in our paper.

Lookups

Querying LSI works in three steps, as illustrated below:

- Query the learned index for an approximate position in the sorted base data.

Again, note that the sorted representation is not actually stored and only

exists temporarily during construction.

- Obtain search bounds based on the approximate position and the learned

index’s error bounds. These can either be guaranteed by construction, as is

the case with PLEX, or could be measured

and retained during training.

- Conduct a local search over the permutation vector to locate the key.

- Lower-Bound Lookups perform a binary search. Note that this requires

O(log k) probes into the base data for a search interval of size k. This

could potentially be prohibitively costly in practice, e.g., when base

data is not fully loaded into main memory.

- Equality Lookups can be sped up by retaining fingerprint bits for each

key and performing a linear scan over the search interval. This requires

O(k) base data probes for a search interval of size k. However, each

additional fingerprint bit roughly halves the number of required accesses.

Evaluation

Evaluations were conducted on a c5.9xlarge AWS machine with 36 vCPUs and 72 GiB

of RAM using four real-world datasets from

SOSD, each with 200 million 64-bit unsigned

integer keys:

amzn book popularity datafb randomly sampled Facebook user IDsosm cell IDs from Open Street Mapwiki timestamps of edits from Wikipedia

All experiments ran single threaded. To prevent skew from potential

out-of-order execution, we insert a full memory fence using the compiler’s

built in __sync_synchronize() after each lookup. A more detailed writeup of

our findings can be found in our paper.

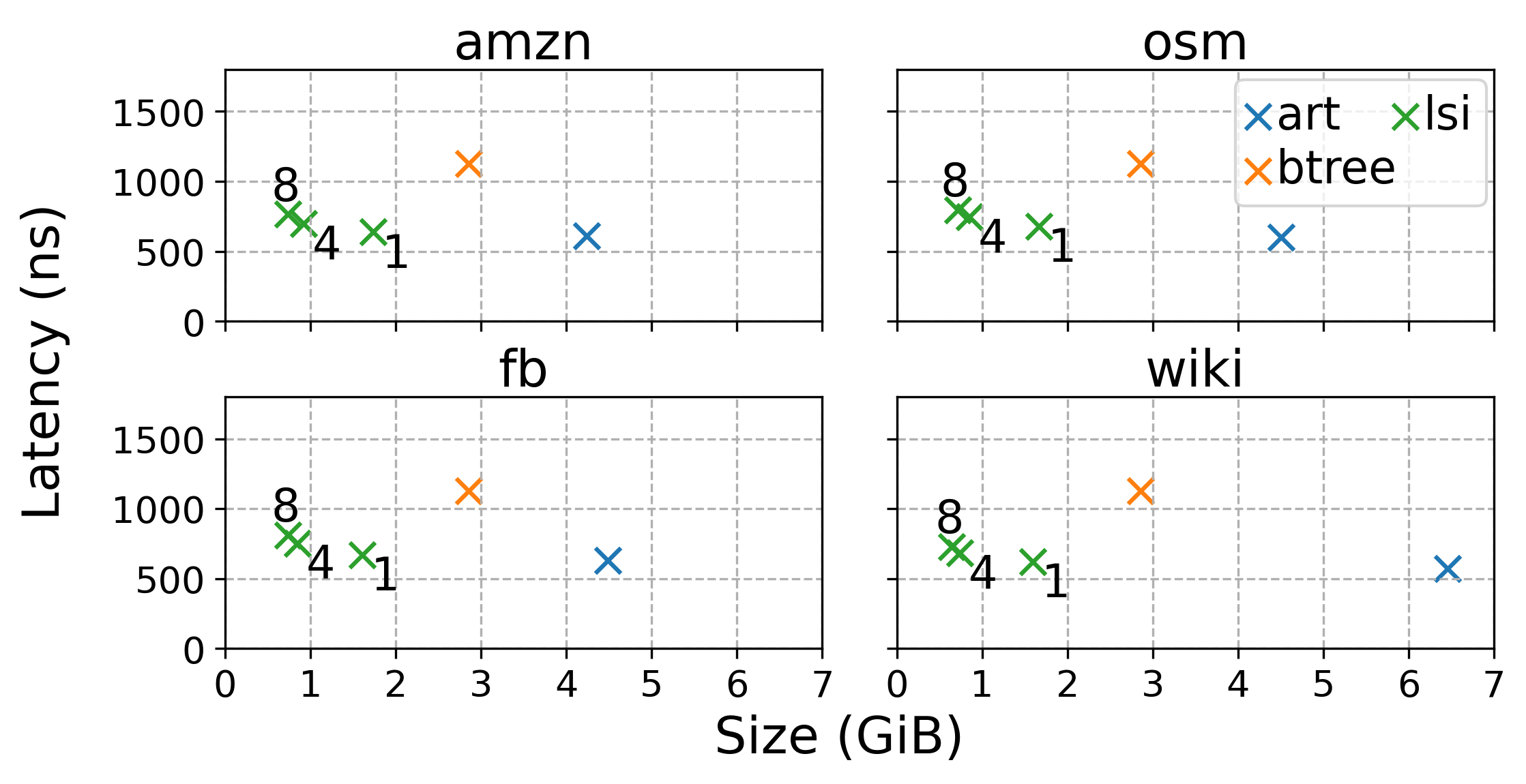

Lower-Bound Lookups

To benchmark lower-bound lookups, we randomly remove 10% of the

elements from the datasets before building each index. We only query for

non-keys.

LSI with PLEX as its approximate index is

competitive with ART’s latency,

while consuming up to 6x less space. It is twice as fast as

BTree while reducing space consumption

by up to 3x.

Note that BTree was constructed by first sorting the data and bulk loading it

afterwards. This enables denser nodes and therefore faster lookups. Inserting

keys in random order one after another increased space usage by roughly 33% and

slowed down lookups by more than 20%. The text annotations denote the LSI

model’s error bound.

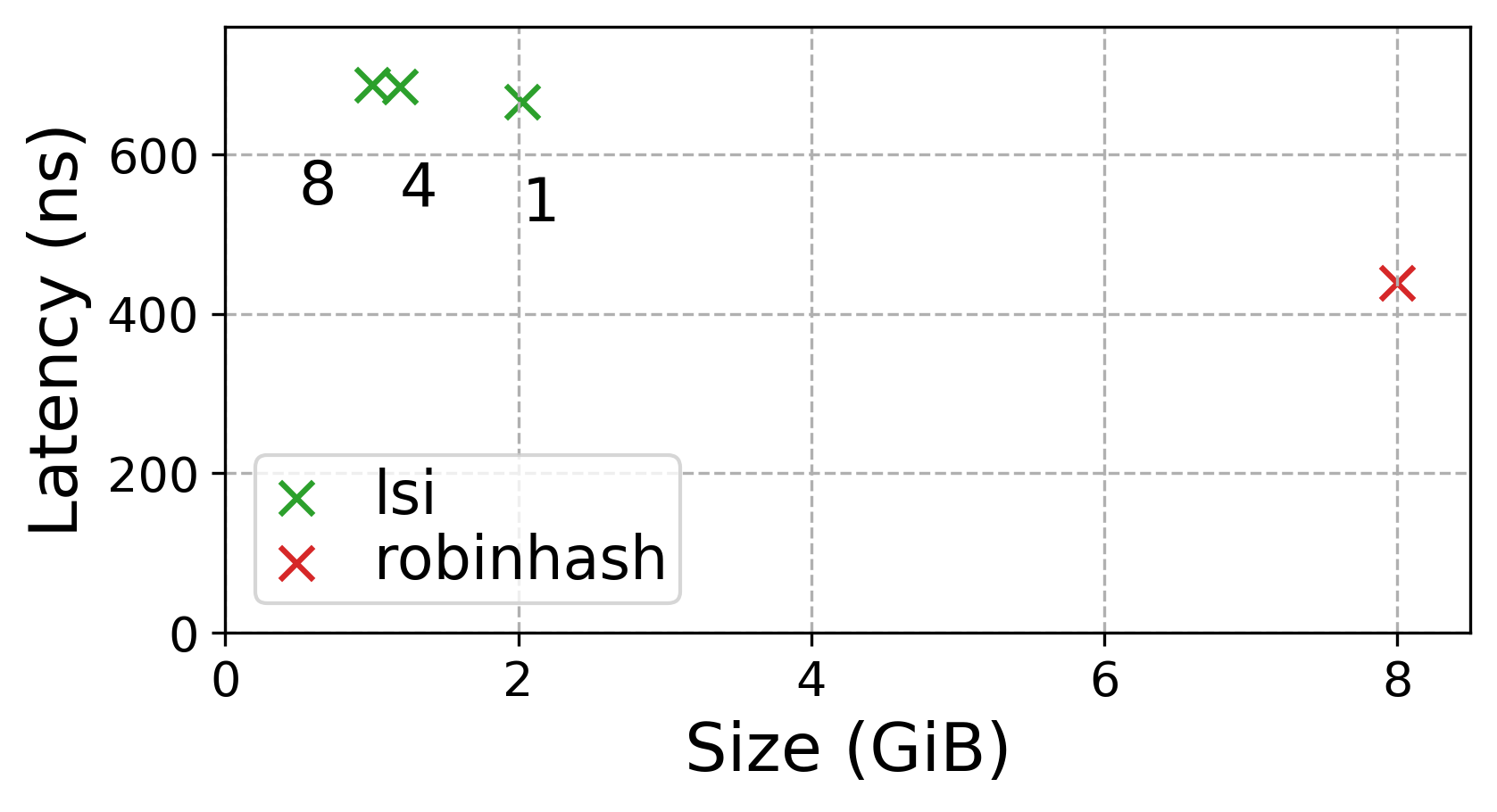

Equality Lookups

Although LSI with PLEX as its approximate

index is around 1.5x slower than the robin-hood hash table implementation

RobinMap, it consumes less than a

quarter of the space. The text annotations again denote the LSI model’s error

bound. Note that we used the amzn dataset for this test, only to later

discover that RobinMap’s hash function appears to be unfavorably biased in

this case. On fb and osm, RobinMap’s lookup only takes 340ns compared to

the 440ns on amzn. Space consumption does not change.

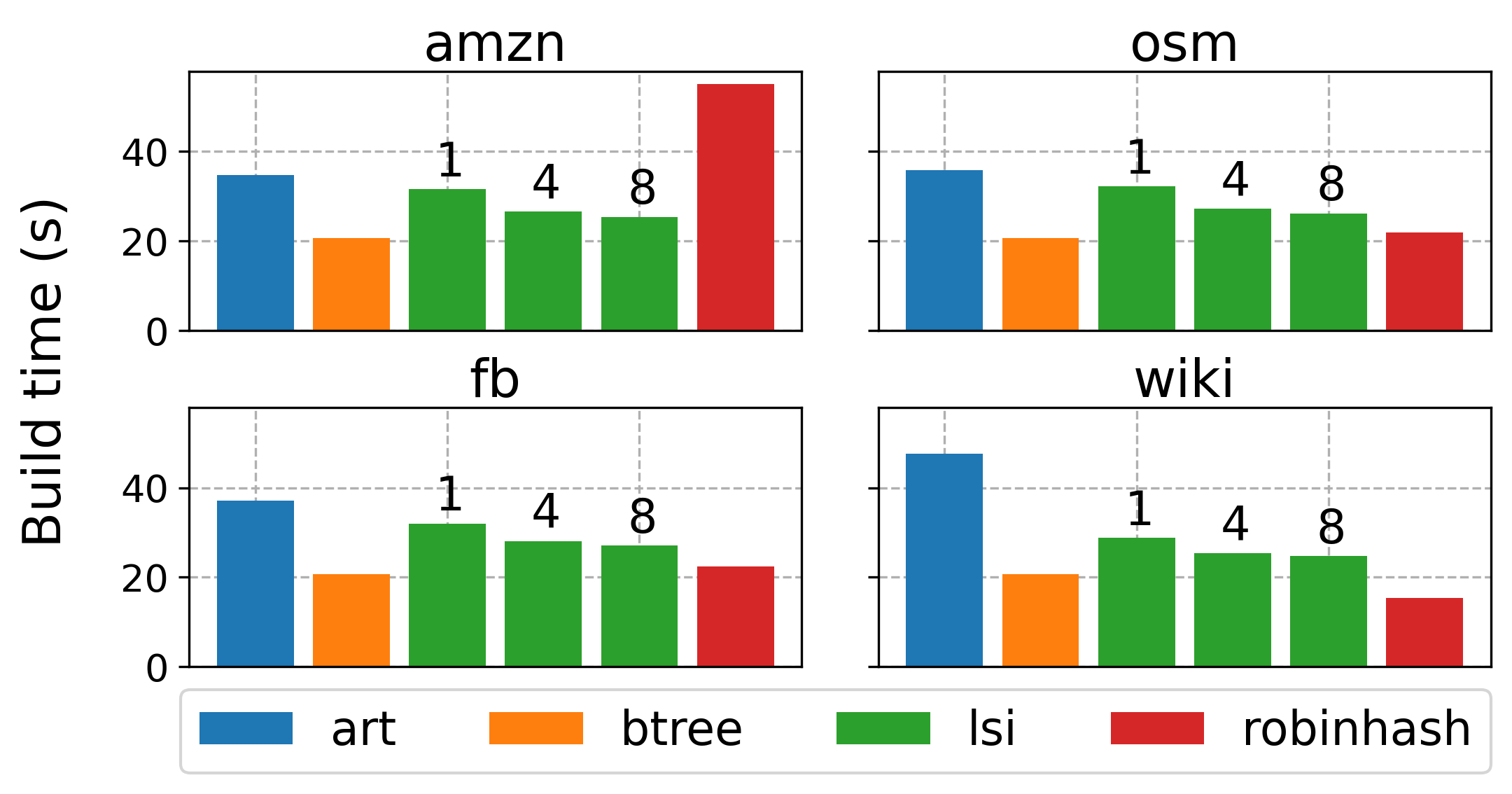

Build Time

We measured the true end-to-end build time for each index given an unsorted

continuous in-memory representation of each dataset’s 200 million keys. LSI is

competitive in terms of build time. It performs slightly worse than BTree, but

surpasses ART on every dataset we

tested. As expected, tighter error bounds on the approximate index increase build

time.

BTree is constructed by first sorting

and the bulk loading all keys. This is about 8x faster than inserting keys

in unsorted order one by one. ART does not have a bulk-loading interface,

however, its construction time is still cut in half when keys are first sorted

and then inserted one after another. We suspect this effect is primarily caused

by better cache behavior during construction.

Note that we would have expected

RobinMap to exhibit equal build

throughput on amzn, fb and osm. Further investigation is required to

determine why it performs so poorly on amzn. We suspect that the hash function,

which we have no control over, might be unfavorably biased in this case. More

than half of all elements from wiki are duplicates. For this reason, build

times for RobinMap on this dataset appear faster.

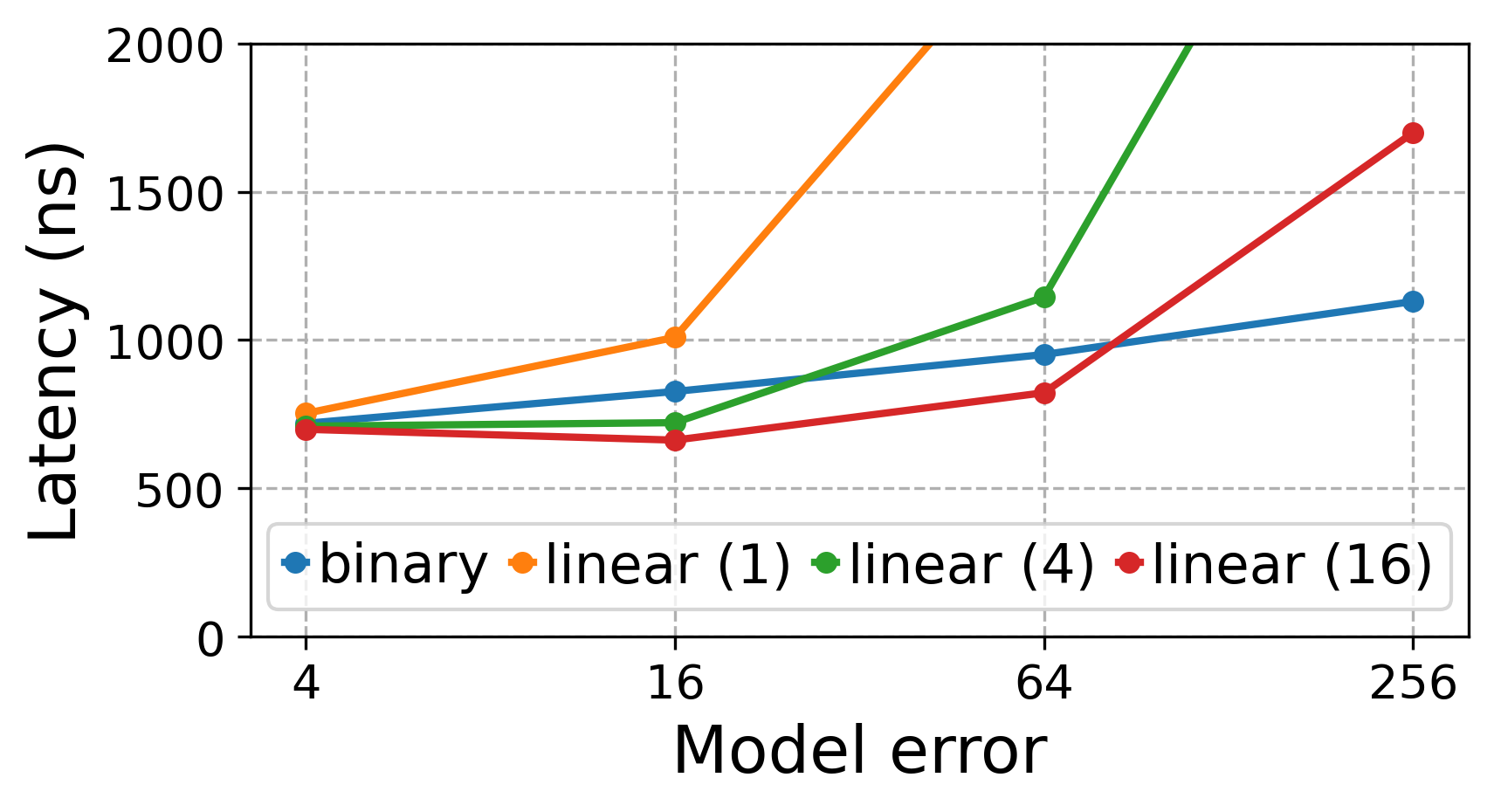

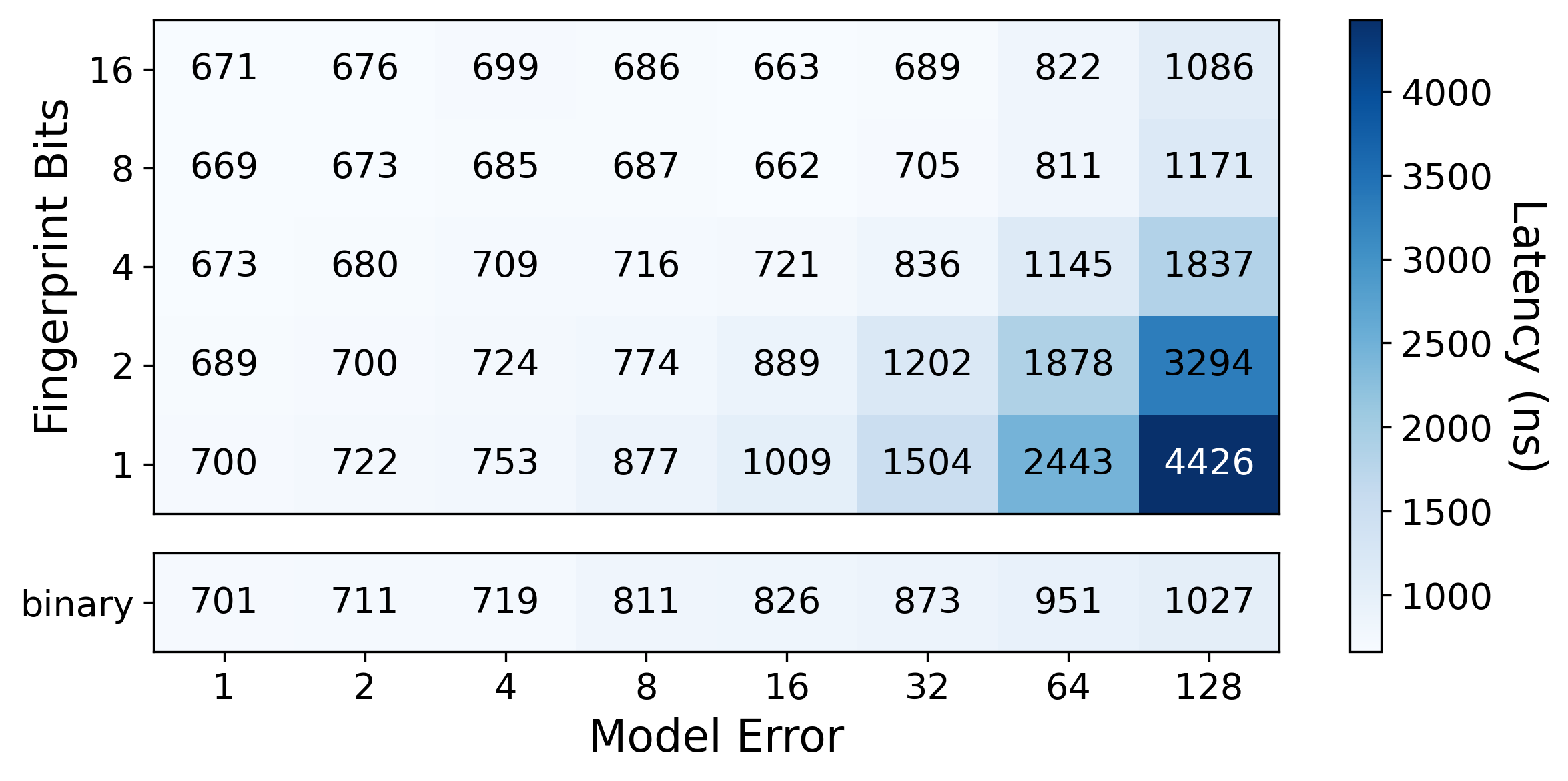

Fingerprint Configuration

We conducted a micro experiment to study the trade off between binary search

and linear search with fingerprints. For this purpose, we trained LSI with

PLEX as an approximate index on amzn

using various errors and fingerprint bit sizes (denoted in brackets), and

compared lookup latencies:

For a search bound of size k, binary search always performs O(log k) probes

into the base data, while linear search requires O(k). Each additional

fingerprint bit will roughly halve the number of base data accesses.

Future Work

We are excited about our promising first results of approaching secondary

indexing using learned techniques. For production readiness, we will need to

add support for inserts. This will require two main adjustments. First, the

approximate index has to be updateable. We could either attempt to extend

PLEX with support for inserts, or use an

existing off-the-shelf model that supports inserts like

PGM. Additionally, we

will have to find a better way to deal with dynamic updates to the permutation

vector. As implemented currently, each update will require shifting and

incrementing values, or O(n) time.

Another interesting direction is to try and reduce base data accesses during

lower-bound lookups. While we could just store a copy of all keys in the

permutation vector, similar to BTree’s leaf layer, this will negate most of

LSI’s space savings. However, there might be an opportunity to store just

enough information to reconstruct enough information about the keys to enable

efficient (binary) searching. Stay tuned!