Author: Ani Kristo

LearnedSort is a novel sorting algorithm that uses fast ML models to boost the sorting speed. We introduced the algorithm in SIGMOD 2020 together with a large set of benchmarks that showed outstanding performance as compared to state-of-the-art sorting algorithms.

However, given the nature of the underlying model, its performance was affected on high-duplicate inputs. In this post we introduce LearnedSort 2.0: a re-design of the algorithm that maintains the leading edge even for high-duplicate inputs. Extensive benchmarks demonstrate that it is on average 4.78× faster than the original LearnedSort for high-duplicate datasets, and 1.60× for low-duplicate datasets.

Background on LearnedSort

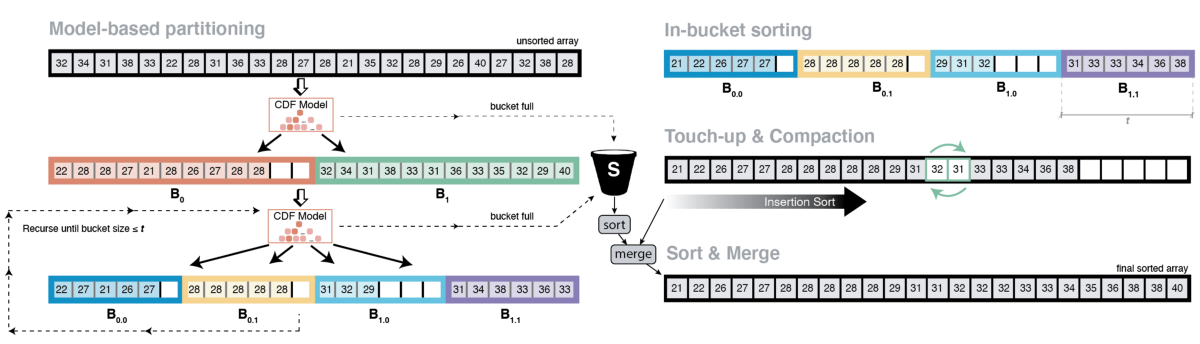

The core idea of the LearnedSort algorithm was simple: we used ML techniques to train a model that estimated the distribution of the data from a sample of the keys; then used it to predict the order of keys in the sorted output. The model acts as an estimator of the scaled empirical CDF of the input.

In order to ensure extremely fast and accurate distribution modeling, as well as effective cache utilization, we designed LearnedSort such that it:

- Partitioned input keys into fixed-capacity buckets based on the predicted values.

- Repeated the partitioning process until the buckets get small enough to fit in the cache.

- Used a model-based, Counting Sort routine to sort the elements inside the small buckets.

- Performed a clean-up step for minor imperfections using Insertion Sort.

- Used a spill bucket that collected all the overflowing keys from the fixed-capacity buckets. This was sorted separately and merged back to the output array at the end.

Eventually, LearnedSort resulted in a very fast, cache-efficient, ML-enhanced sorting algorithm that showed impressive results in our benchmarks. LearnedSort achieved an average of 30% better performance than the next-best sorting algorithm (I1S⁴o), 49% over Radix Sort, and an impressive 238% better than std::sort - the default sorting algorithm in C++. These exciting results also landed LearnedSort a feature in the morning paper.

The Achilles’ heel of Learned Sort

One of the biggest challenges for LearnedSort was the impact of inputs having too many duplicate keys. In such scenarios, the eCDF values for any two equal keys would also be equal. Therefore, the eCDF model makes the same predictions and places them onto the same bucket.

LearnedSort could tolerate a certain degree of duplicate keys; however, this became an issue when the input contained a substantial amount of such keys (usually more than 50%). In this case, certain buckets would quickly reach full capacity and overflow onto the spill bucket, while others would be mostly empty. In turn, progressively more keys needed to be sorted using an external algorithm (i.e., std::sort, which is slower).

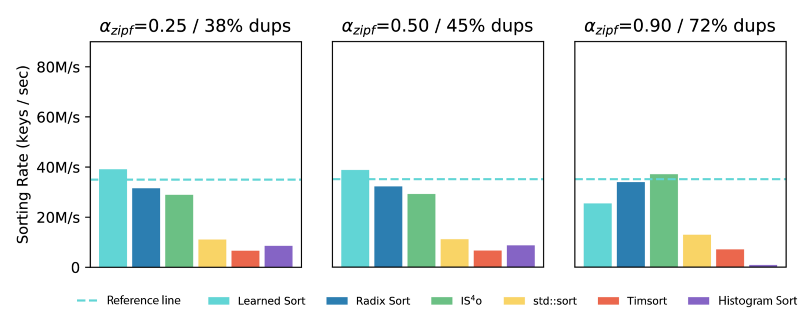

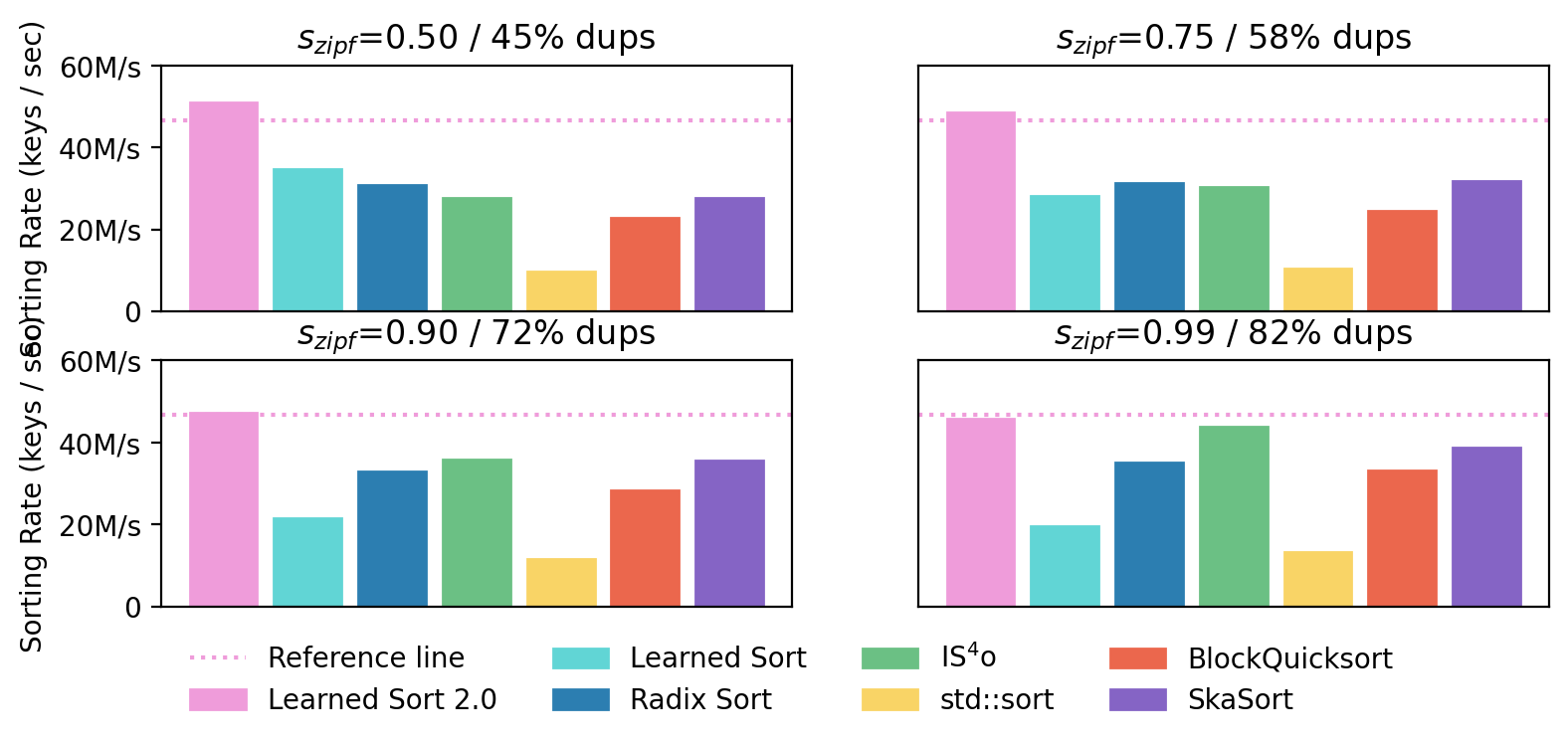

Thus, the spill bucket sorting step became the bottleneck, and the performance of LearnedSort on high-duplicate inputs deteriorated compared to the average case. The figure above shows that LearnedSort’s sorting rate decreases by 22% in the case when the input data had a Zipfian distribution with skew 0.9, which corresponds to 72% duplicates.

Learned Sort 2.0

It was clear that to improve LearnedSort’s performance on high-duplicate inputs, we had to eliminate the spill bucket, and the possibility of bucket overflows. To achieve this, we had to allocate precisely as much space as each bucket needed. One approach is to scan the input and calculate bucket sizes based on model predictions. However, the overhead for this additional step is not insignificant. To mitigate that cost, we could use the training sample for estimating each bucket’s size before allocating. In that case, however, we have to make room for estimation errors by over-allocating, and additional memory acquisition also results in a slowdown.

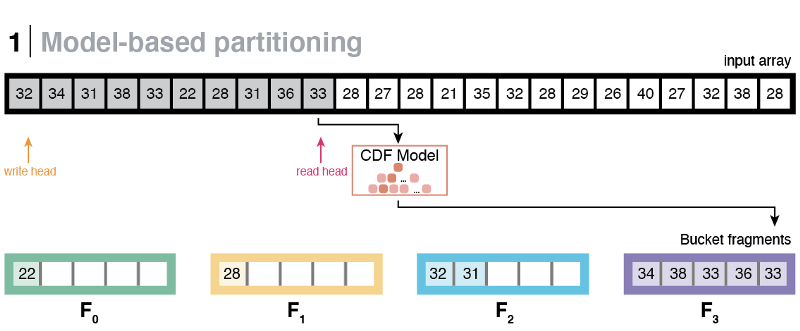

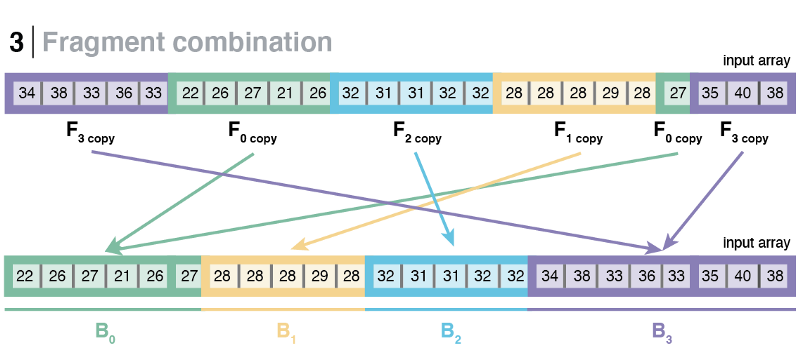

Instead, what worked best was to think of buckets as a collection of smaller, fixed-capacity fragments. The eCDF prediction step would be the same; however, instead of placing the key directly to its predicted bucket, we place it to the corresponding pre-allocated fragment owned by the predicted bucket.

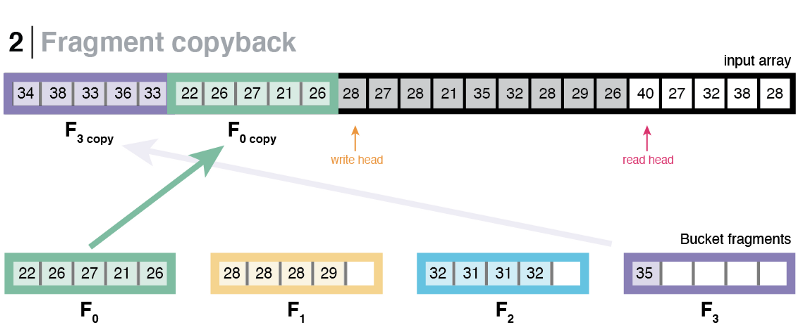

Once a fragment reaches its full capacity (i.e., 100 elements), it is copied back to the input at a given write-head. The write-head is updated, and the copied fragment is cleared to make space for more incoming elements. This procedure continues until the entire input has been processed.

Using this method, we managed to avoid using a spill bucket altogether and logically give each bucket as many slots that they needed, but at the cost of bucket fragmentation. After the first partitioning step has finished, the fragments owned by the same bucket (sibling fragments) will most probably be not contiguous, rather scattered throughout the input array. Therefore, it is necessary to perform an additional step that combines sibling fragments to form a contiguous space that represents a whole bucket.

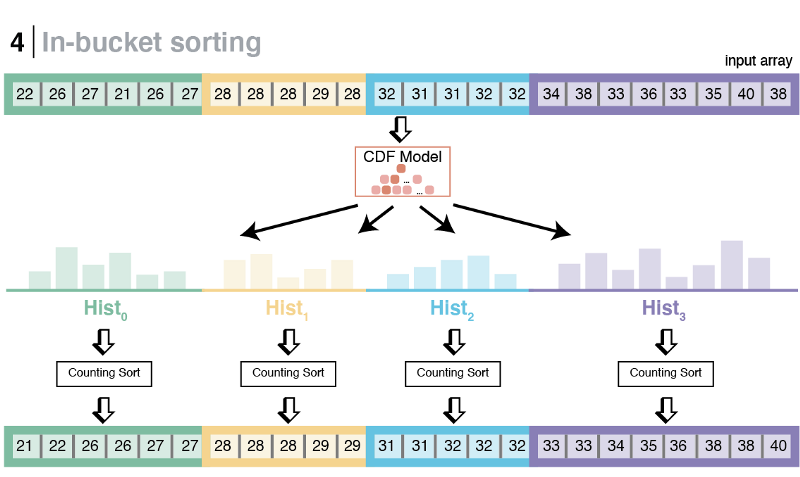

After the buckets have been defragmented, the algorithm will re-partition the keys inside each bucket to further refine the sortedness of the input. This step is similar to the original LearnedSort, and it is done in two steps as a way to maximize data locality and cache utilization. While iterating through the formed buckets, the new algorithm performs a quick check to see if all the elements in the bucket are equal, in which case, it may skip the re-partitioning and jump to the next bucket.

The next step is to do an in-bucket sort using the same model-enhanced Counting Sort subroutine as in the original LearnedSort. This subroutine is fast and has linear time complexity.

Finally, LearnedSort 2.0 still uses Insertion Sort as a final and deterministic touch-up subroutine, which, in almost linear time, guarantees that the input has been monotonically ordered.

Benchmarks

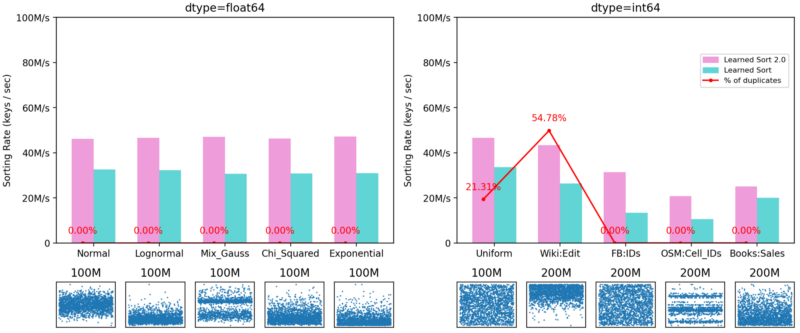

The new design of LearnedSort 2.0 resulted in remarkable performance improvements as compared to the original one. It is on average 4.33× faster for high-duplicate real datasets and 6.57× faster for high-duplicate synthetic datasets. For all other cases, LearnedSort 2.0 receives a 1.60× performance speed-up from the original algorithm.

We first evaluated LearnedSort 2.0 against the original algorithm on ten different datasets. The figure below shows the sorting rate of LearnedSort and LearnedSort 2.0 on a mix of real and synthetic datasets whose majority of keys is comprised of duplicates. In all of the cases, LearnedSort 2.0 gets a major performance boost: It is at least 60% faster than the original LearnedSort (in the case of TwoDups), and on average 378% faster for all these datasets.

In order to further analyze the improvements in LearnedSort 2.0, it is also important to see how the algorithm performs on datasets that LearnedSort was already very good at. We have demonstrated that the original LearnedSort algorithm was the best-performing one in datasets that contained a low degree of duplicates, and this re-design was not aimed at improving in those aspects. Nonetheless, LearnedSort 2.0 still outperforms the original algorithm by an average of 60%. The figure below shows this benchmark’s results.

Finally, we show the performance of LearnedSort 2.0 in comparison with other state-of-the-art sorting algorithms on Zipfian datasets with progressively increasing skew – which corresponds to a higher proportion of duplicates. As shown in the figure below, the sorting rate of LearnedSort 2.0 remains fairly unchanged by the increasing ratio of duplicates, dropping only 3% below the reference line in the case of the highest skew parameter. At the same time, LearnedSort 2.0 leads with the best performance overall, remaining highly competitive with respect to other algorithms even for datasets with a large degree of duplicates.

For more in-depth analysis of LearnedSort 2.0, please check out our Github repo and our new paper, where we give a detailed description of the benchmark setup and show additional experiments on datasets with diverse distributions. We also showed micro-benchmarks to explain its cache efficiency and the improvements from the new design.

Conclusion

LearnedSort 2.0 is a major revision of the original LearnedSort algorithm that builds on its strongest points, while improving on the side-effects of large spill buckets on datasets containing a large portion of duplicates. Here we described the new algorithmic changes and showed benchmark highlights to evaluate its performance. There still remains future work for the extension of LearnedSort on parallel execution models and the handling of disk-scale data.